Overboarding has been recognised as a potential governance issue for some time, with questions over the ability of directors to discharge their duties effectively if they are over-committed to more responsibilities than they have the capacity to manage. As scrutiny increases, this issue has become a greater focus for investors as directors face an ever-increasing set of new responsibilities for which they are expected to provide oversight.

Historically, the responsibilities of board members included participation in regularly scheduled management strategy reviews, often followed by robust debate of such strategy, reviewing of financial statements, assessments of enterprise and industry-specific risks, facing the companies at which they serve, as well as legal compliance issues. However, new threats from a variety of vectors are requiring directors to rapidly become experts in a range of topics in which they have little to no previous experience. Among these new areas of potential risk that boards are increasingly expected to address, we find the most pertinent topics to be:

- cybersecurity risks,

- the impact of disruptive technologies,

- board members’ increasing role in investor relations,

- competitive intelligence, and

- international business experience.

The ensemble of these new responsibilities requires corporate boards to assess the skills set requisite for its own composition in order to remain competitive in an increasingly fierce global environment. The expectations of this type of board accountability, known as “supergovernance”, assumes that board members are capable of peering around every corner in order to counter all possible threats to their company.

Balancing Act

While investor-specific policies towards the maximum number of public boards on which a director should serve are not new, increasing responsibilities for board members are leading investors to re-evaluate their previous thresholds of overboarding. Most prominently, Vanguard, the world’s second largest asset manager, has recently publicly disclosed that its voting policy stipulates to vote against an executive director (defined as a Named Executive Officer who serves on the board at which they hold the role of executive) at any outside board at which they serve. Moreover, their updated overboarding voting policy also states that they will vote against any non-executive director who sits on more than four boards in total at all boards on which they serve.

Blackrock has taken a similar position in its 2019 U.S. voting policy, allowing non-CEO directors to hold a maximum of four directorships in total at public companies. However, Blackrock will still allow a public company CEO to serve on a total of two public boards, and currently makes no distinction in the U.S. between executive directors (other than the CEO) and non-executive directors in the total number of boards on which they may serve.

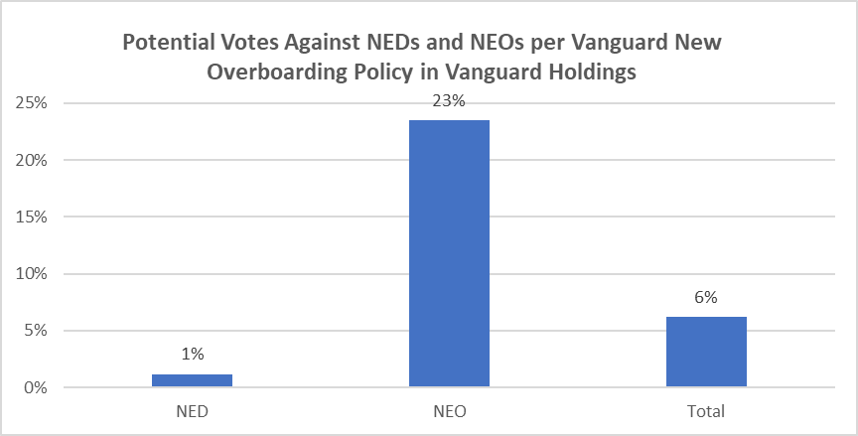

Taking Vanguard’s holdings of 4,861 companies across the U.S., Europe, Canada, Japan and Australia, the CGLytics research team performance an exercise utilizing CGLytics’ data and analytics platform to assess the potential impact of this new overboarding policy on Vanguard’s proxy voting activities. We find that, globally, the implementation of Vanguard’s new guidelines would potentially lead to fairly high levels of opposition, upwards of 23%, for NEO director nominees, who sit on boards outside of the company at which they currently serve as an executive.

Source: CGLytics Data and Analytics

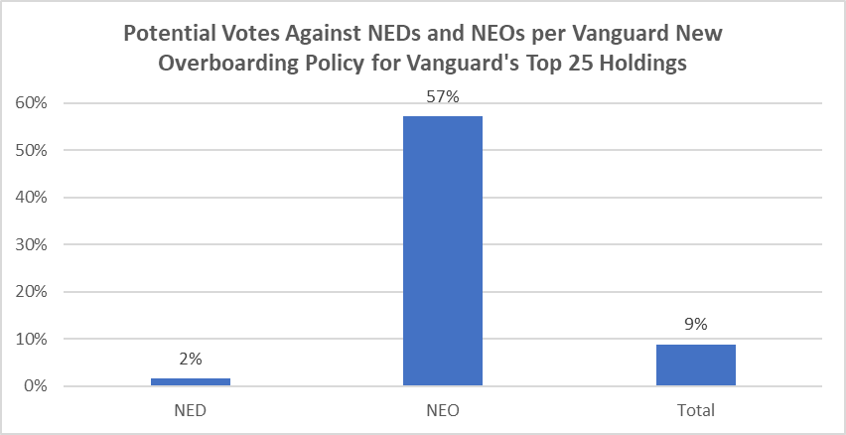

An examination of the current composition of Vanguard’s top 25 holdings also reveals that the implementation of their new guidelines will have an even sharper increase in potential votes against NEOs due to overboarding than during the hypothetical exercise across the full universe of Vanguard’s holdings.

Source: CGLytics Data and Analytics

Not Such a Hard Line

While such an approach may appear rather restrictive for corporate directors and many institutional investors alike, some investors mitigate the perceived severity of this approach by indicating that they will evaluate director appointees who fall outside their overboarding thresholds on a case-by-case basis. Moreover, the language included in their voting policies also makes certain exceptions should the director nominee indicate that she/he will step down from one of the outside boards on which he/she serves within a certain period after their election. Investor engagement also provides corporate directors some leeway, as the issuer-investor dialogue may allow one-off exceptions from opposition to a potentially overboarded director’s election based on the outcome of the engagement.

Finally, the question is raised as to whether these lowered thresholds might benefit corporate board members? Long gone are the days when the expectations for the role of corporate director would be to approve management’s agenda for the company, with cursory corporate oversight capacity. Due to the increasing pressure that board members face in their oversight duties, reducing the number of acceptable directorships from the investor community might provide some breathing room for directors to fully engage in their responsibilities as director. This extra breathing room could potentially allow them to better educate themselves about emerging threats facing the companies on which they serve.

Conversely, the increasing expectations and responsibilities placed on corporate boards often spring directly from the investor community itself. The growing momentum within the investor community implies and often explicitly expects directors to be fully educated on enterprise and material industry risks, as well fully focused on their responsibilities as board members in order to maximize the value of their investments.

As the balancing act between these two perspectives plays out, the issue of potential overboarding for any individual director may prove not to be black or white, but a distinction between various levels of grey. In order to help investors, corporate boards, and executive alike to distinguish between these various shades, CGLytics offers an extensive database with smart analytical tools, to easily screen for potentially overboarded directors. Being able to instantly view the board composition, and that of peers, provides insights into areas of governance practices that may pose a potential risk. In addition, CGLytics’ provides skills matrices to highlight skills and expertise strengths and shortages, director interlocks and smart relationship mapping tools to leverage networking opportunities: all in the one system.

SOURCES: CGLYTICS DATA AND ANALYTICS, FORBES WSJ FORBES

Learn how boards use CGLytics to identify and mitigate governance red flags

Get access to the same insights as investors and proxy advisors with CGLytics’ boardroom intelligence capabilities. With easy to use comparison tools and standardised data, instantly perform a governance health check against regulatory norms and market standards.